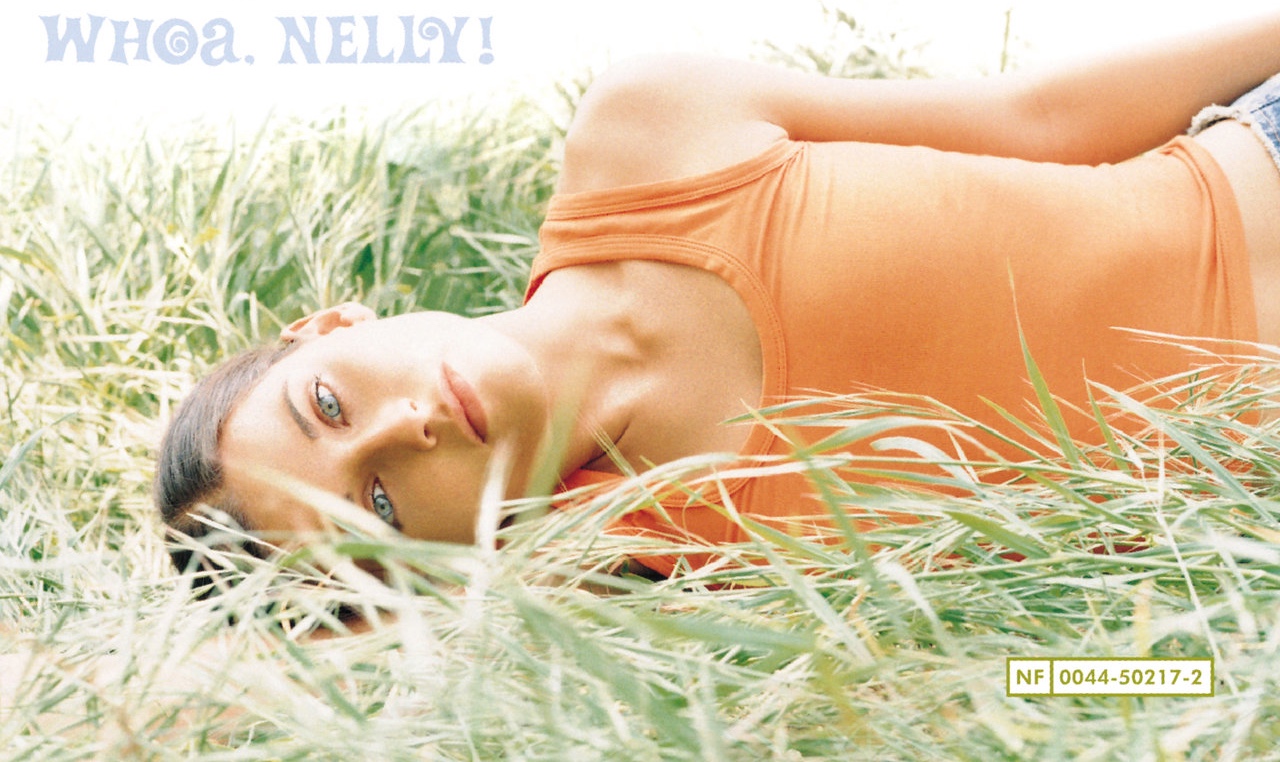

When Nelly Furtado’s Whoa, Nelly! came out in 2000, I was a fourth grader who still had the capacity to be shocked by swear words. That’s one of the first things I remember when I look back on the album’s release and its excellent second track “Shit on the Radio (Remember the Days).” I was one of millions who purchased the album—in my case, begging my mom to buy it for me from a Strawberries sometime after my tenth birthday—and listened to it over and over again, trying to wrap my head around the reaches of her voice, soaring at one point, scatting at another. Each song was sung with the subtle sort of smirk that proved Furtado, as vulnerable as she is in her work, can never really be pegged down.

Whoa, Nelly! is an aughts-era classic that signalled a shift in the kinds of pop stars radio listeners were willing to embrace. Nevertheless, it is often eclipsed in our public memory by Loose, Furtado’s third studio album, largely produced by Timbaland. For many, that album’s hit singles, “Promiscuous” and “Maneater,” marked the arrival of a sexier, more easily digestible Furtado, whom they found incompatible with the artist as they first came to know her. “They sound unlike Furtado not because they’re danceable or sexy—her first two albums were those things—but because they’re about dancing and fucking,” wrote Pitchfork of her new tunes at the time. Audiences loved this album even more than her first two, and Loose remains a critical favorite that has been increasingly appreciated and examined over time.

Contrastingly, the love for Whoa, Nelly!, recorded when Furtado was only twenty-one years old, is hard to come across on its eighteenth anniversary, even with our pervasive cultural nostalgia. That lack of admiration can’t be divorced from the fact that the Furtado we first met was hard to label. She was a pop star, but not a Christina or Britney analogue. Her debut was eclectic, drawing on her roots—her quavering, emotive voice evoking the pathos of traditional Portuguese fado music—among other pop, rock, and hip-hop influences collected from studying music and growing up in Victoria, British Columbia.

But Furtado wasn’t in the same sultry, exotic world Shakira exemplified with her 2001 English-language breakthrough single “Whenever, Wherever.” Furtado was too pop to be an indie music darling (she didn’t play guitar on stage), too eclectic and intriguing to be a pop starlet (she didn’t dance), both talented and unique, but not enough so to be remembered alongside ingenues like M.I.A. or Amy Winehouse. She’s not a Personality, having never been one for tabloids or reality shows, boasting an Instagram account with 126,000 followers and 0 pictures, whereas Shakira is a Guiness record-holder for her massive Facebook following. Her low-key style of fame is, by design, a feminist statement that can be traced directly back to the self she exposed on Whoa, Nelly!: an artist who stands firm in the belief that no person should be reduced to a one-dimensional front.

Furtado’s low-key style of fame is, by design, a feminist statement.

Listening to the album when I was still in grade school, its view of love, relationships, and individuality seemed to come from another world I was only just beginning to understand, far beyond the simplified schoolyard version of romance that flowed from the mouths of other Top 40 artists. “I’m Like a Bird” is a certified bop about fear of commitment and the threat of losing one’s self to loving another person. “Shit on the Radio” tells of dealing with a partner or friend too insecure to handle Furtado’s career success. “Turn Off the Light” covers the fallout after a breakup, the kind of self-questioning that happens after you lose someone you never even fully opened up to.

The album is a takeoff of the girl-power ethos that started with riot grrl and was co-opted by another group of idols from my youth—the Spice Girls. As Furtado explored specific interpersonal intricacies, she also marked a new era of empowering music by women that was as emotionally unguarded as it was danceable. There was something inherently political in the narratives Furtado weaved across the album, too. The line “I don’t want to be your baby girl” on the track “Baby Girl” was as much a statement to the music promotion machine as it was, within the song, directed at a patriarchal lover.

When I unearthed the CD from my parents’ basement a few years ago, I gave the album a relisten (via a streaming app on my phone) to see if it could enchant me again. And while it sounds less deliciously alien to me with eighteen years’ worth of broadened listening tastes, its expression of the complications inherent in being entwined with another person—how it’s almost never as clear-cut as “I love you” or “Now I don’t”—still feels like a revelation.

Today, pop feels less gatekept than it used to. Calling someone “pop” no longer relegates them to the realm of boy bands and J-14 magazine. Lady Gaga is pop. Mitski is pop. Even Cardi B is pop, now that hip-hop is the most popular genre in the country. But women in music are still burdened with pushing back against oversimplified media categorizations, particularly in a time where pithy headlines get more attention than whatever nuanced set of words will follow them.

Eighteen years later, Whoa, Nelly!’s subversiveness is easier to parse. Its influence has come into clearer focus, as female artists, queer artists, and genre-defying iconoclasts pummel expectations of how a popular artist should look and sound. Unlike Furtado, they have a safety net in the Wild West of the Internet that did not exist back when labels still dictated who became famous or didn’t. With her 2017 independent album The Ride, Furtado continues to be every bit as ungraspable as she was in 2000, veering away from the artist we knew on Loose, and embracing sounds as disparate as stripped-down indie rock and industrial-tinged dance music. Critics praised the effort, with Billboard going so far as to call it “the most slept-on release of 2017.” But that ability to experiment was truly honed at the turn of the century with her debut. Whoa, Nelly! may never be celebrated as the work of feminist rebellion that it is—but as Furtado expresses on the album, she wasn’t vying for our approval anyway. FL